The survivor's story is one of the predominant narratives of our time. It usually traces a familiar arc from excess through despair to redemption, and, as such, allows us to enjoy the vicarious thrill of voyeurism within the framework of a cautionary or salutary tale. Life by Keith Richards, the most famous survivor of them all, breaks with this tradition insofar as it contains excess aplenty but hardly any despair and very little redemption. Keith did it all, had a hell of a good time, and survived to brag about it.

Life has the macho swagger that rock'n'roll in general – and the Rolling Stones in particular – once possessed. This is both its strength and its weakness. It often reads like a historical document of another time: a lost world in which women were always "chicks" or "bitches", an inflatable giant penis was a non-ironic stage prop, and a bottle of Jack Daniel's was the de rigueur rock'n'roll accessory.

It is a drug memoir of sorts, albeit without the hardcore confessional descriptiveness of the genre. Instead, it is almost casual in its cataloguing of excess: heroin, cocaine, Tuinal, Nembutal, STP, LSD, speedballs, Moroccan hashish, Jamaican ganja, and, inevitably, methadone, are just some of the substances mentioned – often in passing. Consider, for instance, the following passage from the book, which describes his daily breakfast routine during the 70s: "I would take a barbiturate to wake up … a Tuinal, pin it, put a needle in it so it would come on quicker. And then take a hot cup of tea, and then consider getting up or not. And later maybe a Mandrax or a Quaalude… And when the effect wears off after about two hours, you're feeling mellow, you've had a bit of breakfast and you're ready for work."

The word "mellow" here is, of course, relative. This is someone, after all, who took downers to wake up and start the day – albeit slowly. While reading Life, it is worth keeping in mind that mellow for Keith means comatose for the rest of us. Even John Lennon, no stranger to excess, tried and failed miserably to keep up with Keef, ending up, as the latter puts it, "in my john, hugging the porcelain".

Keeping up with Keef became a deadly game in the early 1970s, when heroin – usually mixed with cocaine and injected as a "speedball" – became Richards and his partner, Anita Pallenberg's, drug of choice.

Pallenberg, alone, seems to have kept up with Keef by being both more ruthless and more reckless. She was originally the girlfriend of Brian Jones about whose death Richards is cold-blooded. Jones, a desolate individual, temperamentally unsuited to fame, drowned in his swimming pool in July 1969, a few weeks after being fired by Jagger and Richards. He is described here as a "whining son of a bitch" whose death occurred "at that point in his life when there wasn't any".

Richards is cavalier about death – his own and others' – seeing it as a kind of occupational hazard best avoided by "pacing yourself". This from a man who scored cocaine and heroin by the pound. It was, he insists, the very best heroin and the purest cocaine, which undoubtedly helped, as did the array of top-class lawyers who were on call every time he ran foul of the law.

The main problem with Life, though, is that too many of these tales have been told before, most evocatively in two classic on-the-road-with-the-Stones chronicles: Stanley Booth's The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones and Robert Greenfield's Stones Touring Party. For me, the writing comes alive when Richards broaches the subject of the great music he once made and the heroes that inspired him to do so.

He is surprisingly illuminating on chord structures and the like, the kind of thing that in most rock memoirs has me skipping pages to get to the next drug bust or wrecked hotel room. He brilliantly summons up the suffocating drabness of postwar English suburbia and the cathartic effect of hearing raw blues and rock'n'roll on imported albums. With Jones and Mick Jagger, he listened to those records over and over, then tried to replicate their sound with the fierce dedication of the true religious devotee. "It was a mania. Benedictines had nothing on us. You were supposed to spend all your waking hours studying Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Little Walter … Every moment taken away from it was a sin."

From time to time, you sense that Richards loved his guitars even more than he loved his "chicks". He sometimes writes about the lure of the Gibson and the Fender with undisguised eroticism. In this, he is the polar opposite of his musical partner, Jagger, with whom he maintains what might in therapy-speak be called a long-term dysfunctional relationship. He has not, he confesses, visited Jagger's dressing room in 20 years.

For Richards, one senses, old wounds are slow to heal. One of the most extraordinary passages in Life describes the writing of "Gimme Shelter" in 1969. It is perhaps the Stones' darkest, most apocalyptic song, but it was spawned, not by the spiralling political turbulence of the times, but Richards's intuition – correct as it turned out – that Jagger was bedding Pallenberg on the set of Donald Cammell's film, Performance.

Richards's relationship with Jagger, though, has outlasted every other relationship either of them has ever had. Neither Richards's heroin addiction nor Jagger's dalliance with the dreadful Studio 54 disco crowd could undo it. The Rolling Stones, too, survive and thrive in ways that it would have been impossible for either of them to have imagined. Now pensioners, they peddle an astoundingly successful global brand of sponsored rock nostalgia – their last tour was the highest-grossing ever. The group's career path perfectly traces the trajectory of the rock form from rebellion, to assimilation by the mainstream, to corporatism; from meaning to empty spectacle.

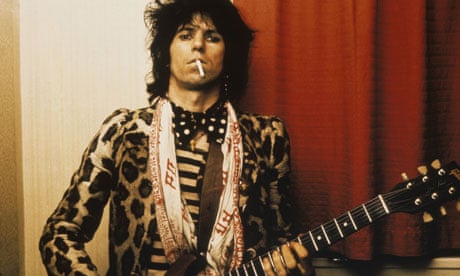

Nevertheless, Keith Richards, now a tax exile and a granddad, remains fixed in the public consciousness as a rock'n'roll outlaw. "People love that image," he muses. "They imagined me, they made me … Bless their hearts. And I'll do the best I can to fulfil their needs. They're wishing me to do things that they can't. They've got to do this job, they've got this life, they're an insurance salesman … but, inside them, there's a raging Keith Richards." That Keith has not raged, nor indeed written a great song, in three decades, hardly matters: he's still here to tell the tale.