Scientist of the Day - Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish pathologist and pioneer of neuroanatomy, died Oct. 18, 1934, at the age of 82. Born in Navarre in Spain, he demonstrated unusual artistic ability as a child, and also a rebellious nature that took him from school to school. He made some drawings of bones for his father, who was a teacher of anatomy, which aroused Ramón’s interest in medicine. He enrolled in medical school in Zaragoza, received his doctorate of medicine in Madrid, then worked in Zaragoza and Valencia. He moved to the University of Barcelona in 1887, and while teaching there, he learned that Camillo Golgi, an Italian pathologist, had invented a way to stain cells with a silver chromate solution, which had the unexpected effect of randomly staining only certain cells, making them stand out against a background of unstained cells.

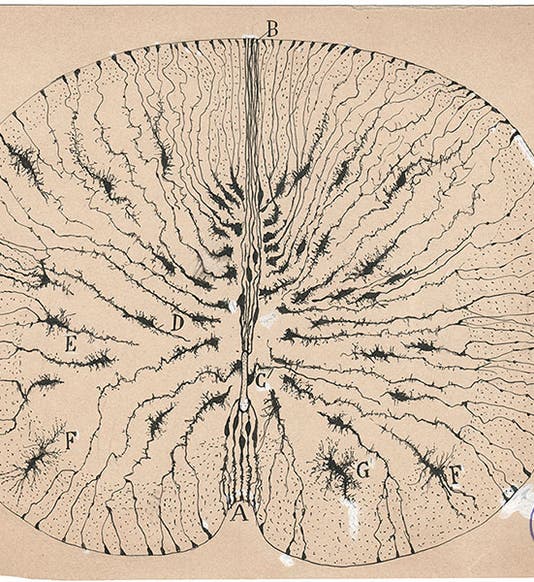

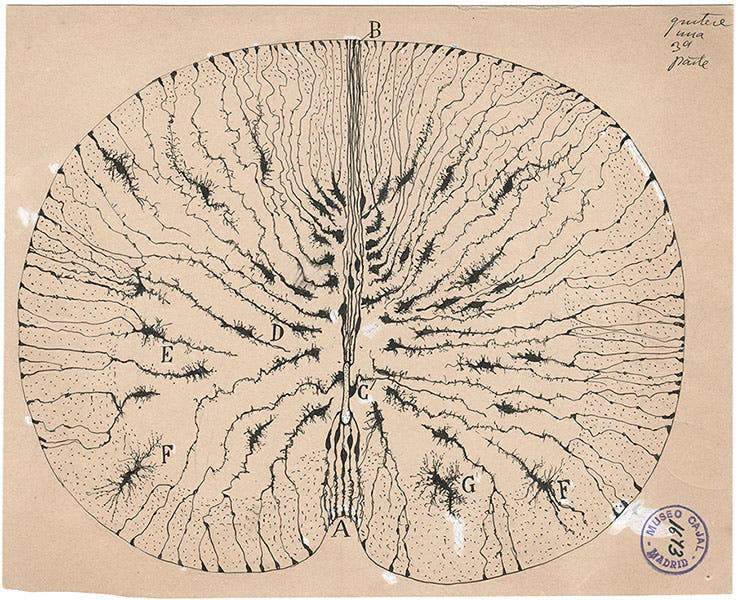

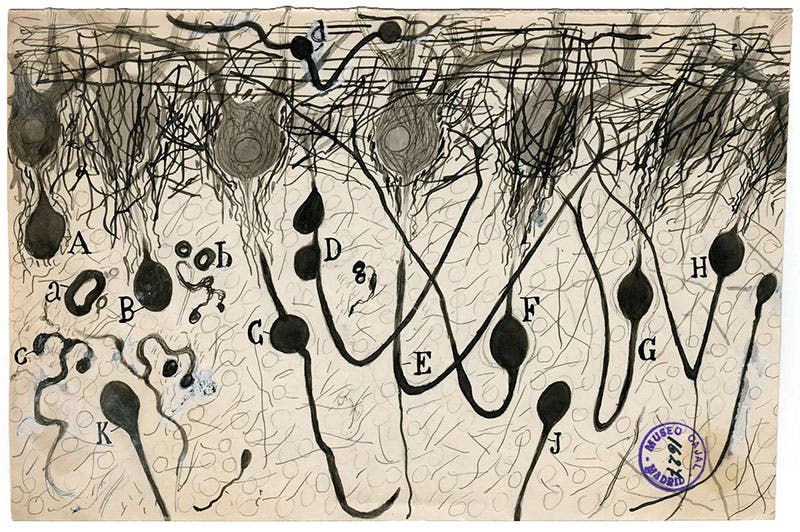

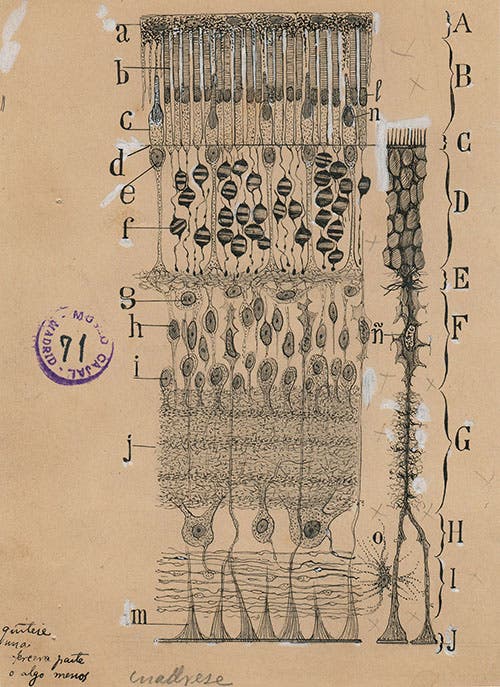

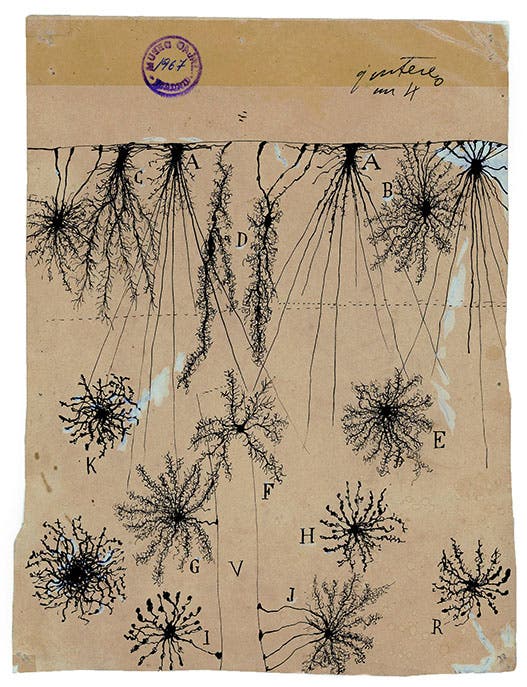

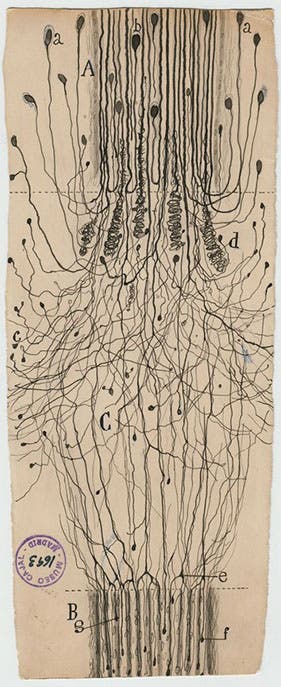

My guess is that Ramón y Cajal was already interested in the central nervous system, but was unable to learn much about it before Golgi's method was invented, since the brain and spinal cord are so densely packed with neurons that it is impossible to unravel their structure without the Golgi stain. Ramón y Cajal began to study nerve cells, recording his observations in the form of exquisite pencil and ink drawings, each of which must have required many hours at the microscope. He moved to Madrid in 1892, where he would spend the rest of his career, and his stack of drawings of neurons and brain sections began to pile up.

When Ramón y Cajal began his study of brain anatomy, most anatomists believed that neurons are physically joined in an intricate neural network. This was called the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal's observations failed to detect any physical connection between neurons. Instead, they seemed to communicate with each other across tiny gaps, now called synapses. The neuron theory or neuron doctrine, as it came to be called, proved to be correct. For this discovery, Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the Nobel prize for Medicine/Physiology in 1906.

We do not collect books or journals in medicine or human anatomy, so I do not know what use Ramón y Cajal made of his beautiful drawings in his medical publications. Nearly all of his original drawings are housed in the Cajal Institute in Madrid. There are over 2800 of them in that collection, but they don't get out much. Fortunately for those interested in the intersection of art and science, a selection of Ramón y Cajal’s drawings went on an exhibition tour in the United States in 2017-18. It began at the Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, and made additional stops at the Grey Art Gallery at NYU, and the MIT Museum in Cambridge. The exhibition was called: The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, and it was accompanied by an illustrated catalog, which I have not seen. Fortunately, the exhibition was reviewed in an illustrated article in the New York Times, and by Scientific American, and these publications (along with good old Wikipedia) provided a source for the images that accompany this post. The New York Times called the exhibition "ravishing," and I have no reason to doubt it.

A cut nerve outside the spinal cord, ink and pencil on paper, drawing by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1913, Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid (blogs.scientificamerican.com)

The New York Times began their review with Ramón y Cajal’s drawing of the cells in the retina of the eye. This seems to be everyone’s favorite Ramón y Cajal drawing, but I thought it would be cheeky of me to copy the NYT too closely, so we have relegated it here to our fourth image. It is quite an astounding pencil-and-ink creation, and really does belong in the lead-off slot.

Ramón y Cajal's drawings of neurons began about the same time that Ernest Haeckel was compiling lithographs of radiolarians and other marine invertebrates for his great work of art and Science, Kunstformen der Natur (1899-1904) , about which we have published a post. It is a shame that Ramón y Cajal did not select 100 of his favorite drawings and publish them for the same reasons Haeckel did, simply because they are beautiful. What an exhibit we could have organized with just those two works!

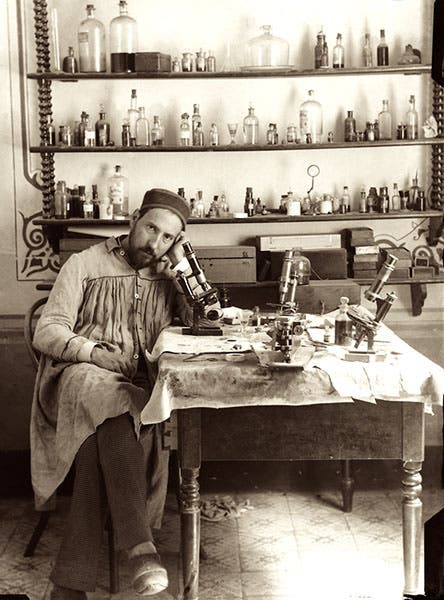

Ramón y Cajal was fond of photographing himself in his lab/studio. We chose one of those for his portrait here, because it is both charming and unusual (third image). If you prefer a more serious conventional portrait, there is one on Wikipedia.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.